We’re often asked for our definition of social entrepreneurship.

In the past three years, our answers have morphed. We started purely on the non-profit side, but encountered problems whereby “everyone” was becoming a social entrepreneur. As we shifted toward the for-profit side, we started to rub up against CSR and social-washing concerns. Instead of broadening our ability to discuss the possibility of social entrepreneurship, we found ourselves increasingly walled within incorporation definitions.

A long time ago, I argued for our ability to hold the broadest definition of social entrepreneurship that we possibly could – so that we might experience and learn from the models holding the greatest yields. And yet, over time, I have found myself sniffing for flaws in business model construction.

- “Is that really social impact?”

- “Is selling to government actually a market opportunity?”

- “Does receiving a subsidy take away the sparkle of the idea?”

Last spring, I joined the Futurpreneur Canada Action Roundtable in Calgary to discuss the needs of advancing entrepreneurship across the country. I listened to entrepreneurs describe their dedication to the community, to their employees, and to creating an organization that was more than just about business (that was about more than just business). They talked about living wages, volunteer days, health benefits, professional development, community engagement, and employee ownership.

When asked as to whether these elements equaled social entrepreneurship, my gut was no, but my head kept asking “why not”? In short, social change was not the goal.

However, when I have looked at social enterprise models with social as the goal, often I am confounded by the use of volunteers or beneficiaries as “staff” or government as the sole purchaser. There may well be social purpose to these organizations, but they lack the elements described above – the social process.

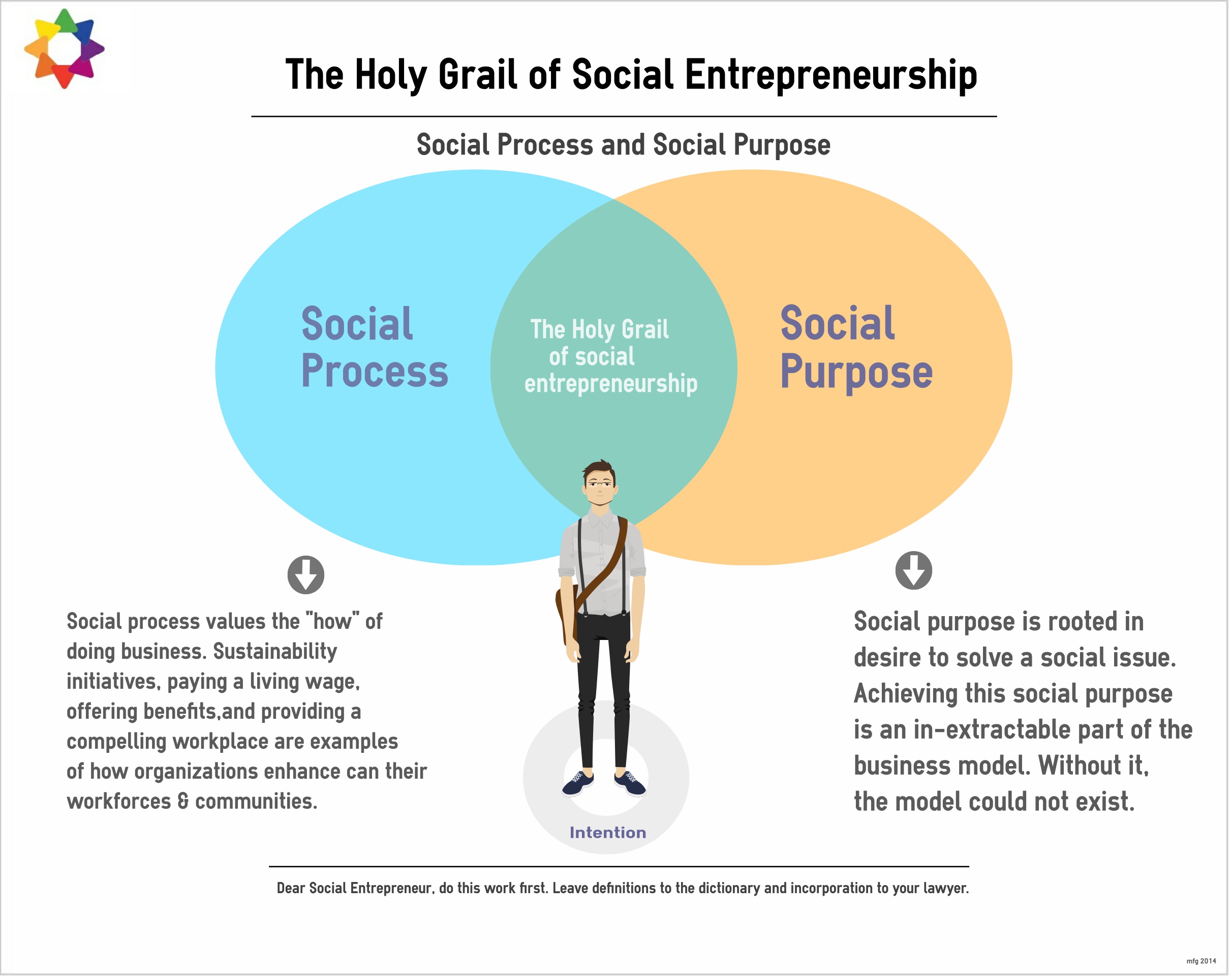

- Social process: Values the “how” of doing business. Sustainability initiatives, paying a living wage, offering benefits, and providing a compelling workplace are examples of how organizations can enhance their workforces and communities.

- Social purpose: Roots itself in the desire to solve a social issue. Achieving this social purpose is an in-extractable part of the business model. Without it, the model could not exist.

Unpacking these concepts required us to start from one vantage point, not definitions, not incorporations, not business models, but rather from “intentionality”.

If we started back at square one, at the point of intention, how should a social entrepreneur start building their business model?

Social purpose + Social process

We offer that social entrepreneurs must know the social purpose they are setting out to solve. Regardless of whether their organizations are selling books, building technology or manufacturing widgets, they must have a clear social purpose they are seeking to solve.

We also believe that they must incorporate social process. Their business model must value the ‘how’ of doing business with intentionality toward their employees and the community. Organizations cannot simply build models that are short termed, harmful to their workforce, or disregard their community.

What is potentially powerful about this view of social purpose and social process is that it is accessible for all organizations. Regardless of incorporation.

Perhaps those playing on purely the social purpose side, see the value of dabbling with a few elements of social process. And those on the social process side, begin to tweak their business models to see where social purpose can enhance their work.

While we’ve built the context of social purpose and social process around social entrepreneurship, the truth is that the power of these two interlinked concepts transcend entrepreneurship. Rather, when placed together, they are the roots of how we can create social change. In any organization – from your local community group to your international ‘big box’ retailer.

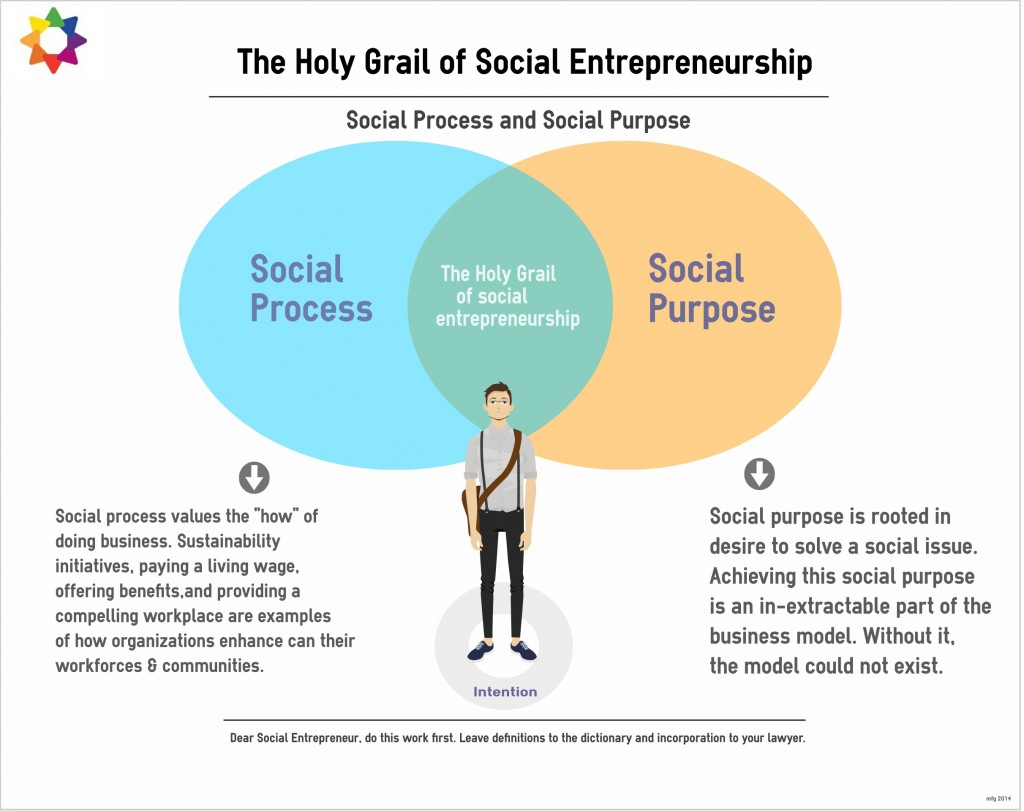

Social purpose + Social process = Holy Grail

At times, we all get so consumed with getting it just right. Within the box. Within the lines. Within the definition. Within the Venn diagram.

Our choice of wording, Holy Grail, is a tongue-in-cheek poke at these notions. That somehow this tiny percentage of shaded area suddenly makes you a social entrepreneur, or worse, that if you actually do find yourself there, you’re somewhat more advanced, special different, anointed than those who do not find themselves there.

And that’s the punchline – there is no holy grail.

The purpose and process will ebb and flow; they will not stay tidily static. For each day of great social purpose, you might lose ground on your social process, and vice versa.

That’s what makes the intentionality so crucial. It keeps you focused when you are building your business model, sourcing your goods, finding your customers, hiring your employees, and selling your services. Your intentionality is the lighthouse for any type of social impact you are trying to create.

Originally published at Trico Charitable Foundation, December 2014.